Story published in Nature Magazine, April, 1948, pp. 181-183,218

and in Steamboat Pilot, May 13, 1948 and May 15, 1959.

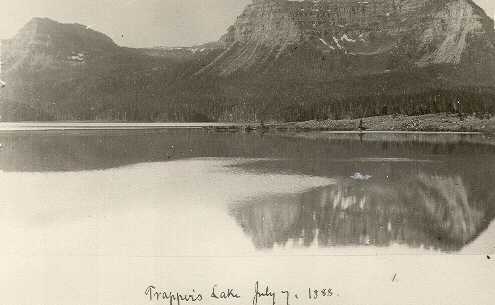

Photo by Henry Pritchett.

Trappers' Lake in White River National Forest, Colorado, in summer, showing the great natural amphitheater formed by the mountain across the lake. The scene was quite different when the author visited the lake and saw spring arrive.

Spring Comes to Trappers' Lake

By LOGAN B. CRAWFORD

Spring had come gently to the Colorado foothills over a period of weeks. The snow had disappeared a little at a time, the water soaking through the slopes or tinkling down tiny creeks with a sound as silvery as the notes of red-winged blackbirds. Even the roar of the river had been only a louder song, growing gradually in our ears and mingled with frog music and meadowlark notes.

But spring came to Trappers' Lake all in a day and a night; in mighty cataclysms with a crash of trumpets and roar of cannons. And there was nobody to see it but me. If I had been a day earlier or a day later, I would have missed it. I had gone to the lake in the Flat Tops that June morning to see if it was time to take native trout spawn for the Steamboat Springs hatchery.

When I left Henry Head, who had driven me as far as the Stillwaters above Yampa, I said, "I'll be back tonight, Henry. You be here to meet me." But I did not get back that night, or for another twenty-four hours. I was a prisoner at Trappers' Lake.

In summer the wild rugged country of the Flat Tops is a fishermen's paradise, for here from deep, clear lakes spring White River, Derby Creek, Sweet Water, the Roaring Fork of the Yampa, and countless other small trout streams. Deer and elk travel the trails through the heavy timber from one grassy park to another, bears wallow in the mud holes, and mountain sheep leap along the high crags.

In winter the place is isolated. Winds whip the snow into fantastic frosting for the great, ten-thousand-foot, white birthday cakes that are the Flat Tops. Some of the frosting never melts the year round.

When I started from the Stillwaters, I carried my skis over my shoulders, for down there it was muddy, grass was growing, and larkspur purpled the hills. As I climbed higher, I ran into snow on the north slopes and in the timber, but it was crusted so hard that I could walk on it. A couple of hours later, when I got "on top," the sun was beginning to melt the crust, and I broke through and had to use my skis. The high country still looked like the dead of winter. The old gray woodchucks that whistled at a fellow in summer were sound asleep under ten- and twenty-foot drifts. Once, on a wind-swept point of rock, I saw a ptarmigan, spotted white and brown, in midseason plumage. Spring must get here some time, I thought.

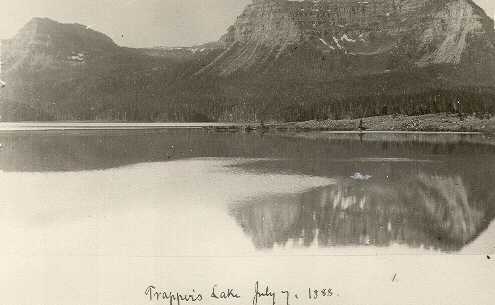

Another view of Trappers' Lake while snow still lingers on the mountains. U. S. Forest Service Photograph.

A warm wind sprang up. The sun, pouring out of a bright blue sky, grew so hot I shed my jacket long before I came to Little Trappers' Lake. From there I slid and plowed my way down a mile or so through the timber to Big Trappers' Lake, reaching there about ten o'clock on that lovely June morning.

Sticking my skis in a snow bank, I stepped upon a strip of bare ground near the tumble-down log cabin some old-timer had built. I breathed a long breath, and just looked. The ice was out of the lake. Calm and deep the water lay, reflecting the great square mountain opposite. The surface was hardly rippled by the breeze. Never before had I felt the stillness so keenly--the thick, furred silence of the forest, the encircling quiet of the scarred white crags. The mountain sheep had had to hunt better pasture; the wild ducks had stopped in lusher ponds; the muskrats and beavers had not begun their summer's work. I did not even see a rabbit.

But there were plenty of trout in the lake. At the inlet from Little Trappers' big speckled beauties, flashing bright underparts, twisted their way into the shallows. I walked as far as I could around the shore, and decided that in another week the boys and I could come and take spawn. Near the outlet, which is the beginning of White River, I scared up a spotted sandpiper, a lone spring arrival. Its plaintive cry hardly made a dent in the monstrous stillness.

In a shady spot on a dry bank near the cabin, I ate the sandwiches I had brought in my pocket and stretched out to rest a while before heading home. The shade kept shifting, and the sun got on me. I remember thinking that sun was as hot as August! I must have been dozing when Boom! went the first cannon, followed by a roar like a rampaging river. I lit on my feet, unable to think what was happening. It could not be a cannon away off here in the mountains. It must be thunder, for it sounded just like a summer cloudburst when lightning strikes a tree. But the sky over the lake was a serene, sunny blue, and cloudless.

Boom! This time I saw a chunk of ice as big as a house break from the cliff to the south, starting an avalanche that took rocks and timber with it. Before the echoes could die another slide let loose, shearing off the Engelmann spruces as if they were grass. A red-tailed hawk came screaming out of the vicinity. Immediately, a mile farther along the mountain, came the jar of heavy artillery, answered, away to the east, by a giant charge. I had seen a few slides in my lifetime in the Rockies, but never a dozen at once. All the length of the mountains that sizzling sun, along with the Chinook wind, was hacking off those big, overlopping drifts like a red-hot knife. Where a moment before the valley had lain in winter quiet, it was now filled with the clang and din of battle.

I thought I had better be getting out, too! But when I put on my skis and struck up through the timber, I discovered the snow had become so soft and sticky that I could no more travel than I could fly. I would have to stay at the lake that night, and climb out on the crust in the cool of the morning.

I went back and stood on the shore, feeling very small and helpless--a mere man in the midst of a mighty upheaval of Nature. I was trapped. There was not a thing I could do about it. Crash! Another monstrous chunk of ice cracked off the square mountain opposite and a new avalanche rocked the basin. Crash! Boom! The distant blasts of breaking ice and the rumble of unseen avalanches told me the same thing was happening for miles around. The old Flat Tops seemed to be shaking their ancient lava bones. Winter was letting loose all holds, and spring was moving in with a tremendous salute.

Wherever a slide plowed a path, a waterfall appeared. Trickles grew rapidly to rivers of white spume. Before my eyes the cliffs were transformed into giant Niagaras as if the scheme of Nature had suddenly been upended, and the valleys had been exalted so that the rivers were now on the mountain tops. Had I been on one of those mountains I would have had good cause to be alarmed, but I knew I was perfectly safe as long as I stayed where I was. Trappers' Lake is six or seven miles around and there was not enough water in the Flat Tops to flood it over its banks. So I thought! To see how much the water would rise I set a long stake in the edge of the lake, notching it with my knife at the present water level.

By mid afternoon torrents were cascading over the cliffs, dashing like ocean spray down the crevices, shattering into rainbows on the talus slopes. There were rainbows--a million of them--in almost any direction I looked. I wished someone else was there to see what I was seeing. Someone who could say, "Yes, that's true!", when I tried to tell about this in the valley. People would think I was exaggerating. I could explain how the unseasonable, smoking hot day, and the particularly heavy load of snow on the cliffs, had combined to produce a spectacle that mortal might never again behold. Words! What I was seeing was a thing to take a man's breath, to rock his very depths.

Stumbling along the shore, my eyes on the display across the lake, I heard a thin high wail, and looked down at the little sandpiper teetering on a rock. "Hello!" I said, glad that he, at least, was still here.

High in the blue the circling red-tailed hawk screamed in outrage. So there were three of us!

Up to the inlet, down to the outlet--a dozen times I made the trip that afternoon, the lonesome sandpiper curveting ahead of me. I could not hear my footsteps in the sand for the tumult about me, although the scream of the hawk pierced everything. A thousand streams blended in one ocean roar. The woods reverberated with it; the sky gave it back, but there was no rhythm to it. And every few minutes came a deafening "explosion." The basin was full of mist. I thought that maybe, when the world was being made, when the land was being separated from the seas, there had been such cataclysmic confusion.

When the shadows fall, this will end, I thought. The melting will stop; the crags will grow quiet; the woods will be at peace again.

I shot a couple of trout for supper. The sound of my gun was puny alongside the cannonading at the cliffs. I cooked the trout on a willow spit and ate them with wood ashes for seasoning.

As the sun went down I looked at my measuring stake and made a new notch. The lake had risen more than a foot!

Any mountain sunset is a thing to fill a man's soul, but what I saw this night was a hundred sunsets rolled into one. I stood in the midst of glory unspeakable while the last long rays from the west flashed red and gold, purple and green, from the streaming cliffs. The waterfalls were like chains of jewels. The whole air was beaded color.

Then night came. The hawk and the sandpiper deserted me. I tried to sleep in the old cabin on a wooden bench because it was dry. Bang! Crash! Boom! The thunder of slides and splintering of ice continued---more awesome in the dark. I had never felt more alone in all my life, and I had slept in the wilds many a night, winter and summer. The bench was as hard as a rock. I went outside, made a big fire in the edge of the timber, cut some boughs for a bed, and tried again to sleep. The stars, usually so big and friendly, over and in the lake, seemed a long way off.

Crash! Crack! Roar! I got up and piled more pitch on the fire. The flames flickered back from the restless water. Ordinarily the splash of a beaver would have been the only sound in the deep mountain silence. Now all I could hear was the rending of trees as more slides knifed the forests. I spent a sleepless night.

Near dawn I imagined that the noises subsided. Surely the melting was over for the air had cooled considerably. I hoped the snow would be hard enough to bear my weight on the trail home.

The snow was not hard, but by daylight I had floundered on my skis up to where I could see the "Chinese Wall," lying east of the lake and extending three or four miles north. Sunrise flamed from a solid sheet of water pouring over the great rock rampart. I could not stop to watch it. Struggling on, I came to the first prong of a creek that I had jumped over coming up. It was rolling along, three times its ordinary size. I took off my skis and waded in, but the force of the water knocked my feet from under me and by the time I had scrambled across and rescued my skis a hundred yards down the hill, I was soaking wet. Within a few feet I reached another feeder to Little Trappers' Lake, and this I knew better than to attempt. That angry white water, roaring through the trees where there had never been a river before, was a fearsome sight. Once more I had to turn back. Now, I thought, I would be unable to retrace my steps, for the first stream was enlarging every second. After desperate jockeying I did get across, and finally returned to Big Trappers' Lake.

Thinking I could escape another way, I plodded around to the outlet. White River, usually a mild stream, was ranting along like the Mississippi. I was still a prisoner.

However, the hot wind had ceased and the new day was cooler. The runoff had been so terrific and so swift that many of the crags that had been snow covered yesterday were now bare. Trappers' Lake was over its banks in several places. According to my measuring stake, it had raised a total of two and one-half feet since yesterday morning! Although the crashes and slides continued at lengthening intervals, the bulk of the water had rushed on down to the valleys. At four o'clock that afternoon I was able to cross the streams to Little Trappers' Lake and make tracks for the Stillwaters. So much snow had vanished that my skis were useless. As I hurried across the high country, I saw a big gray woodchuck blinking on a rock.

"Hi, old timer!" I said. It was good to hear his shrill bark again. Spring had come!

Near dark I reached the Stillwaters where a worried Henry Head had made a second trip to meet me. We had a difficult time driving down to Yampa because mud and water were everywhere and a couple of bridges were washed out.

"I don't know where in Sam Hill all this water comes from!" growled Henry.

Well I knew! I certainly did!

The Steamboat Pilot printed this story May 15, 1959 with the title "When Spring Came to Trappers' Lake" and the following prologue:

This stirring tale of spring arriving at Trapper's Lake was written by the late Logan B. Crawford, son of Mr. and Mrs. James H. Crawford, founders of Steamboat Springs. Logan spent his boyhood and many of his adult years here and was widely acquainted with every part of northwest Colorado. He was a famed hunter, trapper and guide. The story appeared in the August 1949 issue of Nature Magazine, and has appeared previously in The Pilot, but there has been numerous requests it be printed again.

The story by Mr. Crawford:

...